Cognitive Machines and Cognitive Capitalism: teaching the algorithm to see

This is an edited version of my notes for the lecture of my ongoing research on Beauty and the Machine (on machine learning and aesthetics) at the Critical Studies Department of the Sandberg Instituut.

Last year, during the series that I did on the artifice of intelligence here at critical studies, I opened the last lecture of the series discussing Karl Marx so in the interest of continuity, I shall recall this text briefly to bring us back to today or at least to attempt to draw a continuity of my research projects

Between the years of 1857 and 1858 in Fundamentals of Political Economy Criticism, a lengthy and morose unfinished manuscript, Karl Marx wrote:

As long as the means of labour remains a means of labour in the proper sense of the term, such as it is directly, historically, adopted by capital and included in its realization process, it undergoes a merely formal modification, by appearing now as a means of labour not only in regard to its material side, but also at the same time as a particular mode of the presence of capital, determined by its total process — as fixed capital. But, once adopted into the production process of capital, the means of labour passes through different metamorphoses, whose culmination is the machine, or rather, an automatic system of machinery (system of machinery: the automatic one is merely its most complete, most adequate form, and alone transforms machinery into a system), set in motion by an automaton, a moving power that moves itself; this automaton consisting of numerous mechanical and intellectual organs, so that the workers themselves are cast merely as its conscious linkages. In the machine, and even more in machinery as an automatic system, the use value, i.e. the material quality of the means of labour, is transformed into an existence adequate to fixed capital and to capital as such; and the form in which it was adopted into the production process of capital, the direct means of labour, is superseded by a form posited by capital itself and corresponding to it. In no way does the machine appear as the individual worker’s means of labour.

And I want to stress this part:

“the means of labour passes through different metamorphoses, whose culmination is the machine, or rather, an automatic system of machinery (system of machinery: the automatic one is merely its most complete, most adequate form, and alone transforms machinery into a system), set in motion by an automaton, a moving power that moves itself”

an automaton, a moving power that moves itself.

Given that scholars often describe the Fundamentals as the rough draft of Das Kapital, I believe it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that automation was already a preoccupation in Marx theories of labor and capital. And not just any automation but the kind of automatic process that does not require human intervention in order to be completed. Moreover, he continues elaborating on the quality of this machine:

“Rather, it is the machine which possesses skill and strength in place of the worker, [it is the machine that] is itself the virtuoso, with a soul of its own in the mechanical laws acting through it; and it consumes coal or oil just as the worker consumes food to keep up its perpetual motion.”

Now, there is a lot going on here: Marx creates a sort of “workflow” through which he describes how the means of labour go through a metamorphoses so radical, so unprecedented that they become a machine that does not require human intervention. In turn, this machine is described as “having a soul”.

in his conception of capital, Marx talks about a perpetual drive to accumulation. In this conception, he envisions capital accumulation as the operation through which profits are reinvested into the economy, increasing the total quantity of capital (investments as further tool of creation of capital). Capital, then defined essentially as economic or commercial asset value that is used by capitalists to obtain even more value. This accumulation would, of course, impact material conditions and I want to briefly borrow from “The Social Thought of Karl Marx” to get into the heart of this conception of accumulation of capital: materialist theory holds that humans and their interactions are intrinsically organic, physical, and temporal. This means that all human activities and all human societies can be analyzed according to humans’ organic, physical, and temporal characteristics. But, is this conception of sociality still relevant when we are in the age of cognitive machines? How can we situate these machines that Marx anticipated as “having a soul” within this continuum of accumulation of capital?

What are these “cognitive machines”? Rather than resort to academic definitions, I’d rather we focus on what the owners of the means of producing foresight have to say about cognitive machines:

Cognitive machines – these are industry-specific solutions, which are based on a number of core technologies – machine learning, natural speech processing, image recognition – and suitable infrastructure – cloud computing, the Internet of things, big data – and have innovative abilities, which can reasonably be described as higher level cognitive processes. According to a current study their use promises productivity increases of up to forty per cent. Yingxu Wang, Professor of Cognitive Informatics at the University of Calgary, identifies processes of understanding, learning and problem-solving, decision-making, planning, designing and pattern matching, in particular, as “cognitive”. The terms make clear that cognitive machines are – at least according to their potential – not only purely passive tools but self-willed agents, which have “artificial intelligence” and are able to penetrate deep into the fabric of business and society with their actions.

The latest progress in AI is essentially based on learning algorithms, which generate forms of artificial intelligence on the basis of huge quantities of data, making the ability to learn a fundamental product component. We must distinguish between two phases of learning. First, the training phase: during training, the product acquires the critical skills. This is followed by the application phase: the product improves while it is being used. Again, there are two parts to this. Firstly, context learning: the product adapts to the user and the actual context in which the product is being used.

…

Products, which are constantly improving and learning from the experiences of all the people using these products, are products whose capabilities will no longer be determined by the production run but by software updates. Consequently, it is precisely this software and not hardware that will be the critical value driver – regardless of whether we are speaking of wind turbines, air-conditioning systems or smartphones.

technologies used in affective computing will also allow machines to interpret emotional states correctly and react appropriately to the situation on the basis of the sound of voice and the user’s facial expression.

Affective computing: the study and development of systems and devices that can recognize, interpret, process, and simulate human affects.

Manfred Edward Clynes was an Austrian scientist and inventor (who, incidentally, is credited for creating the word cyborg) who developed a way to measure neurophysiology responses to emotions. MIT’s Affective computer lab has created numerous datasets of what they consider the 8 basic human emotions: These eight states (from the Clynes sentograph protocol) are: neutral, anger, hate, grief, love, romantic love, joy, and reverence.

This was the first data set generated as part of the MIT Affective Computing Group’s research. The research question motivating the collection of this particular data set was: Will physiological signals exhibit characteristic patterns when a person experiences different kinds of emotional feelings? We wanted to know if patterns could be found day-in day-out, for a single individual, that could distinguish a set of eight affective states (in contrast with prior emotion-physiology research, which focused on averaging results of lots of people over a single session of less than an hour.) We wanted to determine if it might be possible to build a wearable computer system that could learn how to discriminate an individual’s affective patterns, based on skin-surface sensing. We did build such a system, which attained 81% classification accuracy among the eight states studied for this data set, separating emotions not only on arousal but also on valence.

The data set consists of measurements of four physiological signals and eight affective states, taken once a day, in a session lasting around 25 minutes, for over twenty days of recordings from an individual trying to keep every other aspect of the measurements constant (time of day, electrode placement, eliciting procedure, etc.) The four physiological signals are: blood volume pulse, electromyogram, respiration and skin conductance.

These datasets are now used to train algorithms for the recognition of affect.

trying to understand how cultural analytics would operate vis a vis Barthes’ semiotic codes, particularly in regards to teaching machines to identify highly subjective codes (not even necessarily shared among humans and so heavily dependant on culture/ethnicity/ gender etc). To go back to the previous point about MIT’s “basic emotions”, how are machines trained to distinguish the racial differences in neurological responses (for example, Black men have marked differences in blood pressure in relation to white men or white women; when these neurological responses are measured, which values are taken into account?)

The political implications of teaching these cultural specific aesthetics and affect to machines: Consider how, for example, Instagram’s algorithm “recommends” certain images in detriment of others, how the algorithm deems a photo to be “beautiful” and worth promoting etc

I am interested not only in how these decisions are made (ie a programer “taught” the machine to aggregate specific types of data obviously) but also the taxonomies that went into play for this process and the type of aesthetic choices that are made to create the taxonomies. Not only how “beauty” or “ugliness” are coded into the machine but the cultural aspects of defining these categories.

On the politics of ugliness, Sara Rodrigues et al 2018:

ugliness seems to emerge as a property or attribute of places and bodies rather than as a process that relies on an unjust distribution of value and power in relation to the workings of gender, ability, race, class, beauty norms, body size, health, sexuality, and age.

We position ugliness politically, rather than purely aesthetically, tracing its intersections with discourses, practices, and institutions of power.

Throughout, we focus on literature that is adept at exploring the politics behind the operations of ugliness—that is, work within the fields of feminist theory, critical disability studies, sexuality studies, cultural studies, postcolonial literatures, and critical race studies.

We begin by exploring ugliness as a form of visual injustice, focusing in particular on how ugliness affects relating and how spatio-temporalities are organized to expunge bodies deemed ugly. Following this, we explore the materialization of ugliness through and on bodies as well as in representations.

Theoretical and scholarly work on ugliness has developed along two tracks. The first mostly developed within philosophy, elaborating upon ugliness as an aesthetic category opposed to beauty. This body of work suggests that ugliness is the direct opposite of beauty and that the two qualities are properties of seeing.

Such a view tends to naturalize ugliness as a property of objects, people, places, and of the technology of sight. The philosophical engagement with ugliness also binds its analysis to the examination of art and literature. We are interested in disassociating our project from the philosophy of aesthetics to pursue a more politicized understanding of ugliness and to consider how categories of ugliness are interlaced with and deeply underwritten by ability, age, gender, race, class, body size, health, and sexuality.

Critical disability studies theorist Tobin Siebers argues that while philosophy has sought to disembody aesthetics, aesthetics is inherently political and embodied. Tracing the notion and discipline of “aesthetics” to eighteenth- century philosopher Alexander Baumgarten, Siebers asserts that “aesthetics […] posits the human body and its affective relation to other bodies as foundational to the appearance of the beautiful”

Borrowing from Rodrigues text, I invite you to politicise aesthetics and to critically examine every Instagram algorithm recommendation.

Today, we experience art in collaboration with these algorithms. How can we disentangle the book critic, say, from the highly personalised algorithms managing her notes, communications, browsing history and filtered feeds on Facebook and Instagram? She exemplifies what philosophers call the extended mind, meaning that her memories, thoughts and perceptions extend beyond her body to algorithmically mediated objects, databases and networks. Without this externalised thinking apparatus, she is not the same critic she would be otherwise.

if the algorithm is an externalised thinking apparatus, basically, teaching the algorithm to see means teaching the algorithm capitalist value: this is worth seeing, this is worth ignoring, this is beautiful, this is ugly, this thing needs to be protected or cherished, this can be discarded, this person is ugly, this other person is non compliant etc etc.

It is here that I unequivocally observe that the algorithm itself becomes a key organisational structure: what I mean is, the taxonomies that determine what we see have been drawn from our own cultural values (and the concomitantly perceived as lacking in value) but at the same time, they operate as a super structure that perpetuates these values unexamined and offer a bureaucratic organisation for our aesthetics choices. “this is pretty, look at it” says the algorithm and this statement does not exist in isolation: it exists as part of more than 500 years of intergenerational utterances of “this is pretty” or “this is ugly”.

The algorithm, as organisational structure also becomes a structure of administration: “this is pretty, look at it”, functions in an attention economy where influencers and marketing organisations earn a living producing aesthetically pleasing content, as a form of administration of the capitalist value.

of course, the algorithm as organisational and administrative structure is evident in fields such as healthcare (for example, where the algorithm “denies” treatment to a patient based on certain data points such as financial situation, life expectancy, age, etc). However, it is not merely an evidently biopolitical interface for the administration of life but a totallizing structure that informs our leisure, social relations, love life or art appreciation.

A quick recap is in order: this current research is a continuation of last year’s project about “the coloniality of the algorithm” that situated Linnaean taxonomies at the heart of both colonial history and our contemporary uses of technology.

Thinking of how colonisers, upon meeting native americans or Black African women superimposed their aesthetic values on their bodies. It wasn’t long ago that beauty contests were reserved to white women only. From the Smithsonian Magazine Archive (emphasis mine):

Since its inception, the pageant has evolved in some ways and not so much in others. The talent competition was introduced in 1938 so that perhaps the young women could be judged on more than just their appearance, but with that small bit of progress came regression. That same year, the pageant chose to limit eligibility to single, never-married women between the ages of 18 and 28. The kind of beauty the pageant wanted to reward was very specific and very narrow—that of the demure, slender-but-not-too-thin woman, the girl next door with a bright white smile, a flirtatious but not overly coquettish manner, smart but not too smart, certainly heterosexual. There was even a “Rule 7,” abandoned in 1940, that stated that Miss America contestants had to be “of good health and of the white race.”

I would add: it is not merely that the people who make programming decisions for algorithms are biased but that the building blocks of these technologies are based on data fields and taxonomies that were, from their inception, a project of exclusion. It is not just that humans enter their own biases into algorithms but that the entire field of data collection is a perpetuation of colonial biases that have never really gone away.

So, in this context, I am also interested in the idea of the simulacrum: how do machines learn what is real vs what is simulacra? (Side note for Blade Runner’s machines themselves being the simulacra) particularly because this distinction anchors our notions of purity and “realness”. Through the simulacrum, we expose the mechanisms through which we judge something pure or impure, fake or real.

Entrupy’s CTO and co-founder, Ashlesh Sharma, completed a PhD at NYU specializing in computer vision, which allows computers to capture an object’s microscopic surface data. Sharma saw the potential to use this technology to map what Entrupy calls the “genome of physical objects.”

“The genome of physical objects”

Interesting to me is that the founders published a paper with the title “The Fake vs Real Goods Problem: Microscopy and Machine Learning to the Rescue” and that machines are being trained to detect simulacra at microscopic level. From the paper (again, emphasis mine):

we introduce a new mechanism that uses machine learning algorithms on microscopic images of physical objects to distinguish between genuine and counterfeit versions of the same product. The underlying principle of our system stems from the idea that microscopic characteristics in a genuine product or a class of products (corresponding to the same larger product line), exhibit inherent similarities that can be used to distinguish these products from their corresponding counterfeit versions.

thinking of Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition, particularly “simulacra as the avenue by which an accepted ideal or “privileged position” could be “challenged and overturned” and simulacra as “those systems in which different relates to different by means of difference itself”. Especially in terms of class issues surrounding counterfeit goods, how if the simulacra is “too good”, it shatters the class signifier through which “different relates to different” (ie rich signaling their wealth to fellow rich). But, on the other hand, if the simulacrum can only be detected at microscopic level, how much of a simulacrum is it (at least in terms of delivering the class signifier its meant to deliver)? ie if the copy cannot be detected with the naked eye, if it looks authentic and serves the function for which it was created, then what is real?

Deleuze: “The simulacrum is not just a copy, but that which overturns all copies by also overturning the models”

and

“Does this not mean that simulacra provide the means of challenging both the notion of the copy and that of the model?”

Again, from the paper (emphasis mine)

In the counterfeiting industry, most of the counterfeits are manufactured or built without paying attention to the microscopic details of the object. Even if microscopic details are observed, manufacturing objects at a micron or nano-level precision is both hard and expensive. This destroys the economies of scale in which the counterfeiting industry thrives. Hence we use microscopic images to analyze the physical objects.

The authors of the paper describe this process as “feature extraction”.

“Feature extraction”, I want to put a finger in this notion of extraction because if the cognitive machine is good at something, it is precisely this.

In “Settler Colonialism as Structure”, Evelyn Nakano Glenn writes:

In classic colonialism, the object is to exploit not only natural resources but also human resources. Native inhabitants represent a cheap labor source that can be harnessed to produce goods and extract materials for export to the metropole. They also serve as consumers, expanding the market for goods produced by the metropole and its other colonies. Goods and raw materials, like colonists, follow a circular path in classic colonialism.

Extractivist practices have been extended to include not merely the physical (ie natural resources) but also data and intellectual property.

In that sense, the algorithm serves a double function:

it extracts data

it protects capital (by detecting the simulacrum)

also, worth noting that the simulacrum “devalues” the original by allowing access to the aesthetics of the real to the class of people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford it. while “the fake” could be seen as having a democratising effect, the algorithm is deployed to maintain the strict class divisions that only money can transcend. in that sense, the simulacrum devalues and corrupts the aesthetics of a certain class even if simulacrum and real are identical to the naked eye. I would go as far as saying that the class division is then maintained at microscopic level.

and on the issue of class, a rhetorical question I’ve been asking for a good while now: who owns the robots? of course I am talking about algorithm ownership as the new means of production (the hardware itself being easy to reproduce/ scalable enough that it is not out of reach etc). With the algorithm, of course: the database, the information itself. once extractivism runs its course, the progression to the intangible, attuned to a world running out of physical resources to extract. Production then not just as a physical task but the body as data (what we consume/ health metrics/ movement/ genetic information/ preferences etc)

And again, I insist on robot ownership as a metaphor for the way these cognitive machines, this superstructure of administration and organisation operate because I want to bring attention to the several issues that permeate my research, namely:

the algorithm as an epistemic and pedagogical interface (we teach the algorithm to see and, in turn, the algorithm teaches us what is worth seeing, a perpetual motion of both teaching and learning the same desire(s); an ouroboros of aesthetics and capitalist value)

but also, as capitalism reaches resource scarcity, we shift the ownership from material resources to ownership of knowledge itself. To quote Yann Moulier Boutang, the French philosopher who coined the term, Cognitive capitalism is not only a type of accumulation oriented towards the valorisation of knowledge and innovation. It is also a new mode of capitalist production.

Matteo Pasquinelli in “The Eye of the Algorithm: Cognitive Anthropocene and the Making of the World Brain”

Cognitive capitalism and cognitive Anthropocene

From an epistemological point of view, it is not arbitrary to establish a parallelism between the protocols used to intercept and ‘forecast’ anti-social behaviours and terrorism and the protocols used to intercept and ‘forecast’ the anomalies of climate change.

it is not an extrapolation to add that these same protocols are equally deployed to forecast aesthetic choices. Appreciation of beauty (or ugliness) is not merely the realm of humans.

In a study published last year, researchers from Cornell University examined racial bias on the 25 highest grossing dating apps in the US. They found race frequently played a role in how matches were found. Nineteen of the apps requested users to input their own race or ethnicity; 11 collected users’ preferred ethnicity in a potential partner, and 17 allowed users to filter others by ethnicity.

Even the way the food we eat looks like is influenced by algorithms: the pervasive nature of Instagram has meant that restaurants and cafes are creating dishes to cater specifically to instagram users so that the photos get more recommendations, increasing the exposure of the cafe to attract more customers.

I took this photo in Lisbon last weekend. This cafe offering a menu identical to the menus found in any other city the world over. “optimized” not only for tourism but for a specific kind of tourist that seeks to photograph their “fashionable” food. Cognitive capitalism requires a portable, global aesthetic that can easily be reproduced everywhere. The english language is not the only hegemonic factor in these developments, a uniform look facilitates data aggregation as well. It reduces the number of specificities and variables that would have to be indexed. Even though pancakes are consumed in different forms the world over, the pancakes optimised for Instagram are of a specific type: American, piled on top of one another, dripping with syrup etc. Restaurants change their interior decoration to be more appealing for Instagram: white marble tables, sleek surfaces.

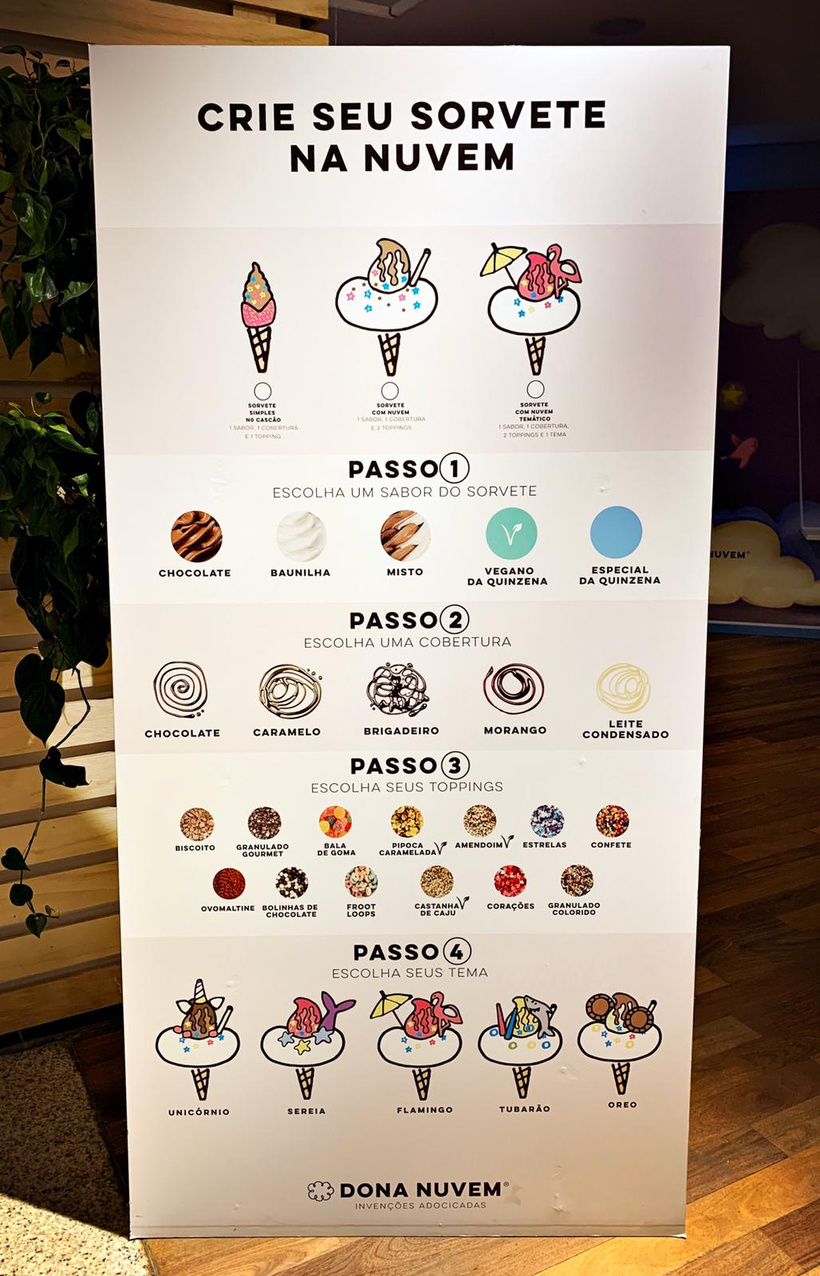

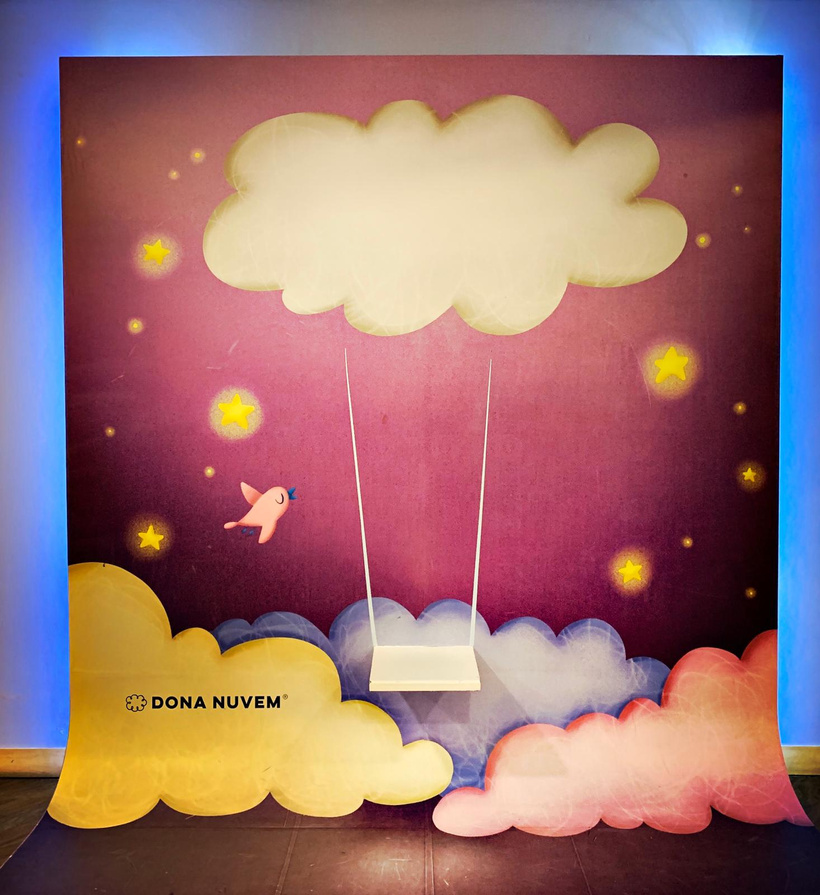

In Sao Paulo there is even an ice cream shop that was created with the express purpose of selling ice creams and providing backgrounds that would look good on Instagram. I took these photos this past summer and I didn’t even capture all the aesthetic possibilities that the place offered to customers. There were more backgrounds and more props available. You’d notice the bright colours which are also not gratuitous: apparently, Instagram is optimised for bright colors.

“There is a growing number of people who will judge food based solely on a photo, which is a little crazy,” said James Lowe, head chef and owner of Lyle’s in east London.

And he adds: ”It’s led to chefs doing what I call ‘cooking for pictures’ – which is where someone will put a dish together without any concern for whether or not is actually tastes good, just as long as the aesthetic is right.

A moment ago I invited you to politicise aesthetics and to critically examine every algorithm recommendation. I was, of course, recalling Walter Benjamin’s seminal work on the aestheticization of politics and his insistence on the politicization of aesthetics that he associated with a revolutionary praxis or a redeeming force.

In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” a priori Benjamin seems to be mainly concerned with aesthetics. He focuses on “the aura”. For Benjamin, the aura is an unassailable kind of aesthetic presence of art practically rooted and anchored in religious experience. He mourned the development of film and photography that eliminated it, leaving behind an experience devoid of the sublime. However, while he lamented this loss of aura, he also described something new, a kind of intersubjective experience, of an object gazing back at us. Benjamin was, like Baudrillard or Deleuze would be a few decades later, concerned with authenticity and simulacra. If the aura was lost, what replaced it was a new aesthetic experience, one that was no longer rooted in the sublime but that exploited capitalism’s need to position the individual as an isolated unit, self contained, separate from the rest.

and here I have to make a very quick detour that would be a topic for its own lecture, “the selfie” as the mode of expression of a cognitive capitalism that requires this individual alienation. Not only the selfie as the portrait of the self (to be obvious) but also the paradigm of individual photography. For further context, I’d like to recall Mehita Iqani & Jonathan E. Schroeder’s work on “#selfie: digital self-portraits as commodity form and consumption practice”:

Selfies are media commodities in two ways. Firstly, all users of Facebook and Instagram (and similar applications) are enrolled, knowingly or not, in a corporate owned service, which is ultimately profit oriented and sells advertising space. Apart from an expressive consumer practice, we can think of the selfie as a branding tool, a market research technique, and a social media content generator. Secondly, the self-portraits turn the image of the self into a commodity that is made public and consumable by others, projecting personal images into collective space and literally “sharing” very widely self-produced messages. Considering the aesthetic properties of selfies, it become clear that they are a unique visual genre with particular forms of use and exchange value. As Paul Frosh argues, the selfie is a “gestural image” that cannot be theorized in purely aesthetic terms; it is also social and informational

If Benjamin’s lament about the loss of the aura and the replacement of the sublime with the mass produced invited us to politicise aesthetics, the underlying concern of Benjamin wasn’t so much about aesthetics but mostly perhaps, an ethics of art production and reproduction. We live in the post age of mechanical reproduction when these cognitive machines and their algorithms can infinitely reproduce our cultural foundations on a never ending loop. We taught them what to see and now, like in a fever dream, they continuously remind us of what we value, what we discard, what we appreciate or what we hate. “Look at this, this will please you” they say but all we see is a mirror.

For the past decade and a half I have been making all my content available for free (and never behind a paywall) as an ongoing practice of ephemeral publishing. This site is no exception. If you wish to help offset my labor costs, you can donate on Paypal or you can subscribe to Patreon where I will not be putting my posts behind a lock but you'd be helping me continue making this work available for everyone. Thank you. Follow me on Twitter for new post updates.